DNS Importance With WVD

So by now you’ve probably heard of WVD (Windows Virtual Desktop) as it’s one of the fastest growing services in Azure, especially since it went GA back in September 2019!

When WVD went GA the WVD Gateways were only deployed in the following locations:

- United States

- Europe

But as of today (18/01/2020) WVD Gateways are available in the following locations:

- United States

- Europe

- Japan

- India

- Brazil

- Australia

- Asia Pacific

So as you can see, within the space of around 4-5 months (following the teams announcements at Ignite 2019), we have a good spread of WVD Gateways all across the world!

The above map was taken from the Ignite 2019 slides (thanks Microsoft), hence not showing all as GA; but trust me they are and you can see that on the WVD roadmap here

But I thought this post was about DNS…?

Hold fire, it is; but first I just need to set the scene a little more around the WVD service and how connectivity to your WVD Desktop or RemoteApp actually works behind the scenes.

WVD Client Connectivity Explained

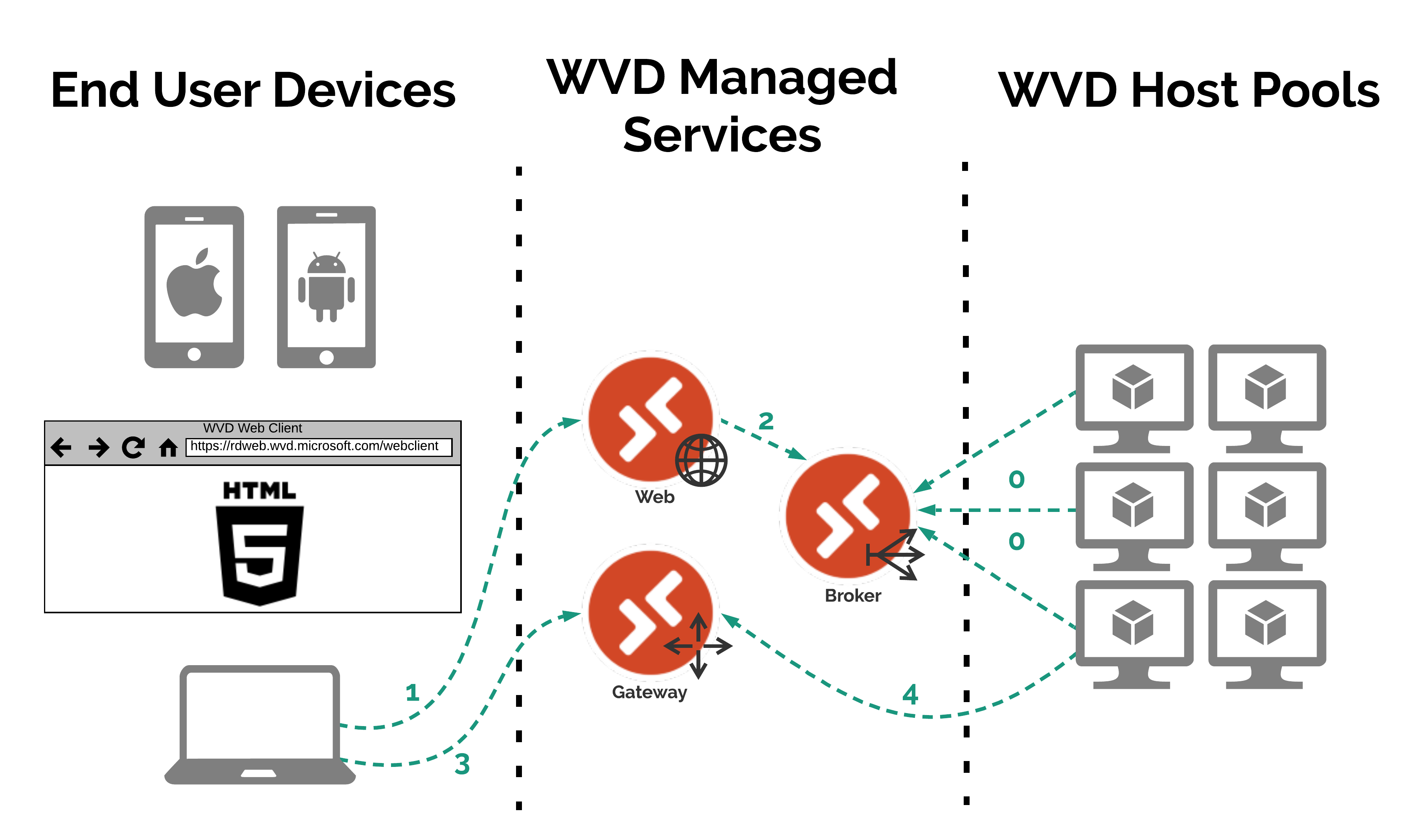

From a very high level the below diagram should explain how a end user device connects to their require WVD Desktop or RemoteApp.

Steps Explained

- WVD Host Pool VMs connect to the WVD Broker service and report their status (if they didn’t no Desktops or RemoteApps would be available to connect too)

- An end user device makes a connection to the WVD Web service to authenticate against Azure AD and once logged in to be presented with the relevant Desktops & RemoteApps the user is able to connect to based on permissions etc…

- The WVD Web service connects to the WVD Broker service to check what Desktops & RemoteApps should be shown to the user

- When the user selects the Desktop or RemoteApp they wish to connect to, they are connected to a WVD Gateway service

- The WVD Broker service instructs a Host Pool VM to connect to the same WVD Gateway service to complete the Reverse Connect Process

As you can see from above the end user device makes 2 connections outbound to the WVD service.

- 1 to the WVD Web service: to authenticate the user to the tenant and also to present the Desktops and/or the RemoteApps for the user to select to connect too.

- And the other 1 to the WVD Gateway service: this actually does the Reverse Connect between the end user device and the WVD Host Pool VM.

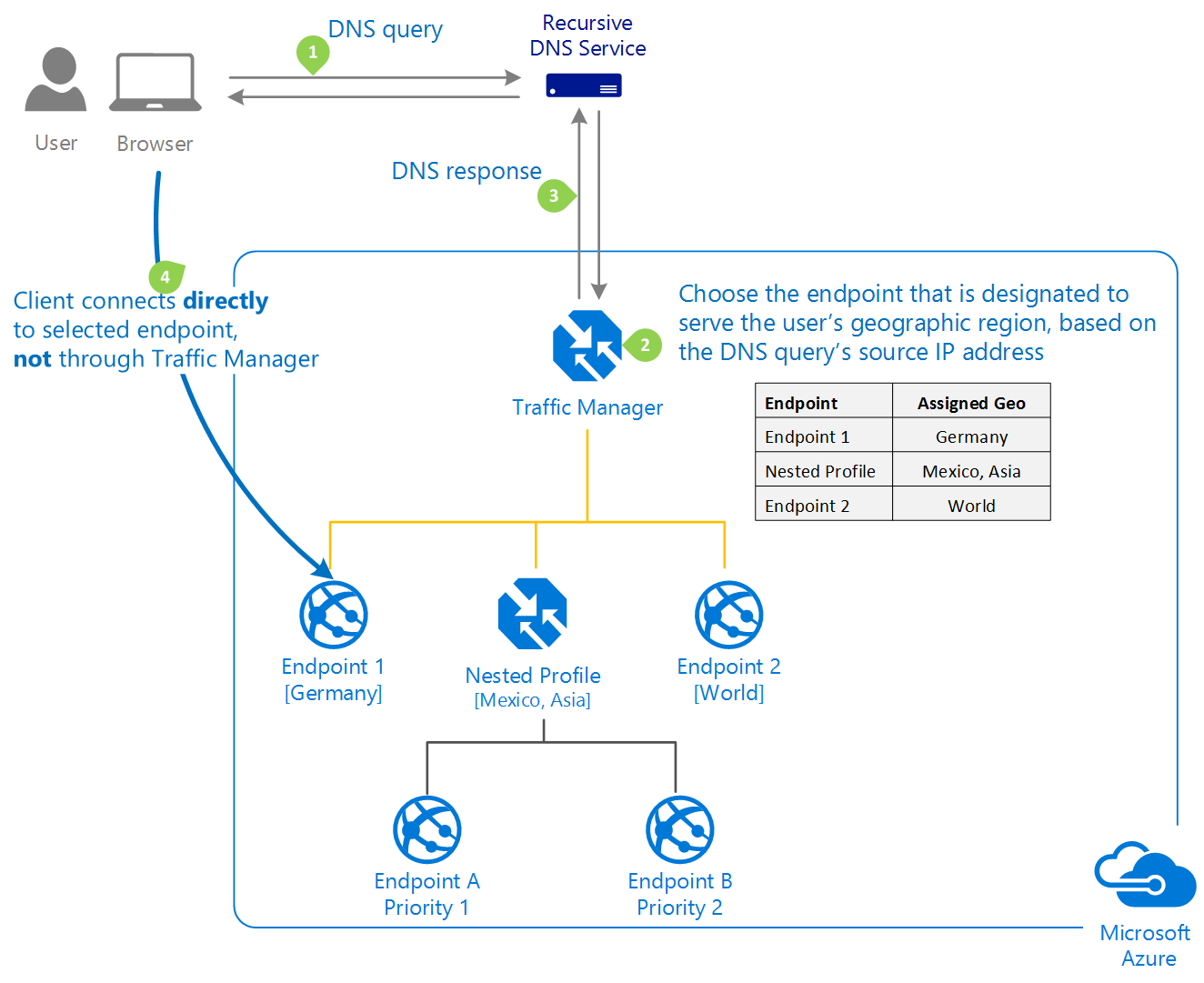

Both of these connections are first GSLB’d by an Azure Traffic manager that’s sits in front of both the WVD Web and Gateway services.

The Azure Traffic Manager then decides which of the WVD Web and Gateway deployments around the world to connect your end user device too.

How does the Azure Traffic Manager make it’s routing/load balancing decision for the WVD Web & Gateway components…?

As the below diagram shows, its all done at the DNS level. The Azure Traffic Manager doesnt actually pass or handle any client traffic it just returns a DNS record based on the routing method configured on the Traffic Manager Profile.

For the WVD Web & Gateway services the routing method is set to Geographic. More detailed information about how Traffic Manager works in general can be found here on the Microsoft Docs site.

Step 2 is the crucial part to understand here for WVD!

As step 2 says, the endpoint is chosen based on the source IP address of where the DNS query originated from.

This means that based on what DNS server your end user device is configured to get DNS from, and the DNS server that your corporate DNS server is probably forwarding DNS requests too, the user could be connected to a WVD Web & Gateway service that actually isn’t anywhere near them geographically.

Therefore the latency, performance and general experience for the end user could be heavily impacted by something as simple as DNS!

Here’s an example

This example is probably more relevant to an enterprise environment, but it will still demonstrate the potential issue.

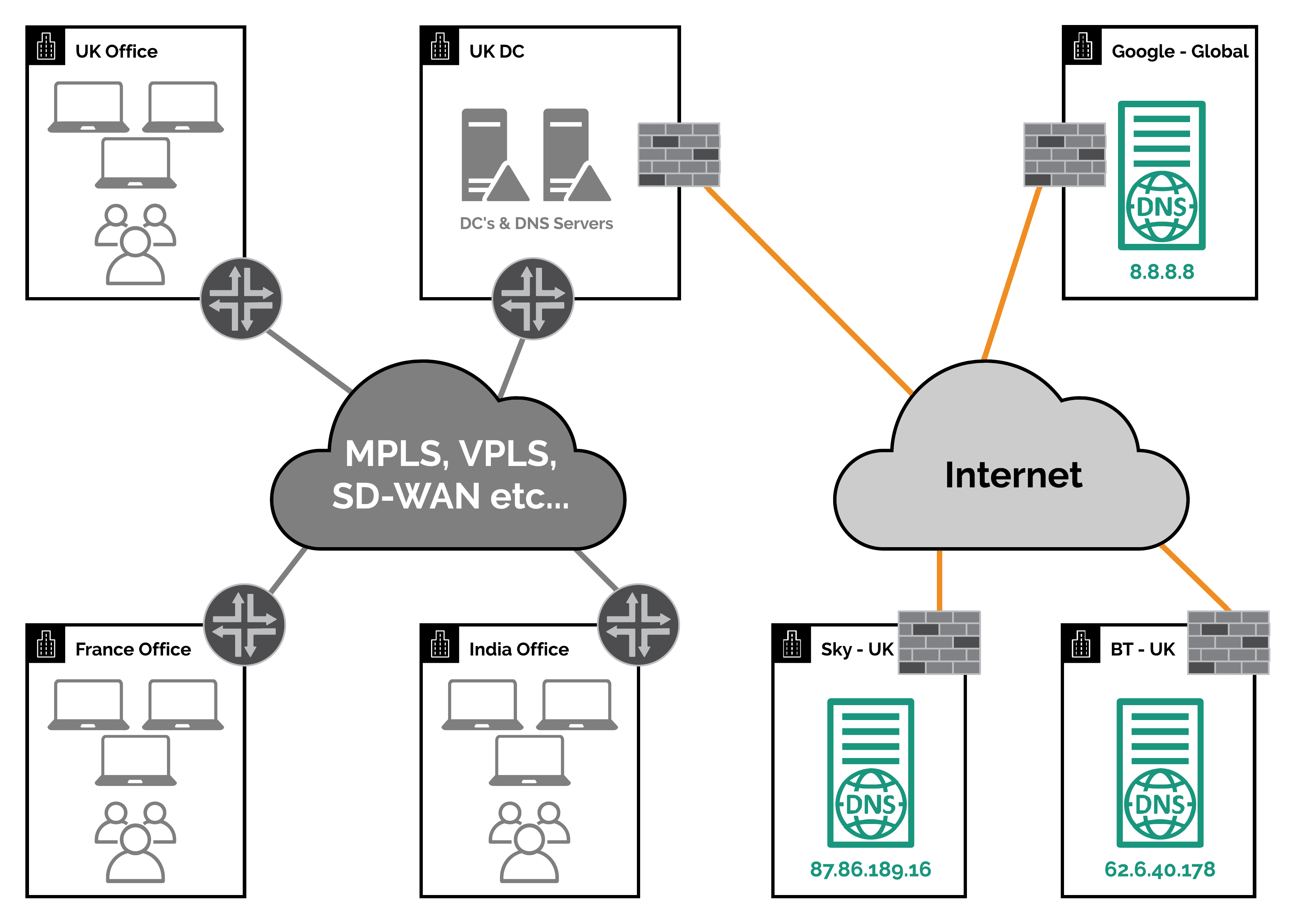

So first of all lets take a look at the above diagram and use it as the basis of a couple of scenarios that I will go into below.

WVD DNS Scenario 1 - The Bad

For this scenario lets assume the following:

- All offices and their devices are using the DNS servers in the UK DC which they access over their corporate WAN

- The DNS servers in the UK DC are forwarding DNS requests to the BT & Sky public DNS servers over the internet

- No DNS records are cached

In this scenario when a end user device tries to access the WVD Web or Gateway services it will make a DNS request to find the IP address of the services.

In this scenario the DNS request process from the client will proceed as follows:

- The end user device will check it’s DNS cache = no record found

- It will then forward the DNS request to one of the DNS servers in the UK DC

- The DNS server in the UK DC will check it’s DNS cache = no record found

- The DNS server in the UK DC will forward the DNS request to either the BT or Sky public DNS servers

- Either the BT or Sky public DNS servers will send a DNS request to the Azure Traffic Manager fronting either the WVD Web or Gateway service

- The Azure Traffic Manager will check the source IP address of where the DNS request was made from to it. In this case it would be either the BT or Sky public DNS server IP addresses

- The Azure Traffic Manager will then lookup this IP address against its Geo database and decide which region it has come from. In this case it would be the UK/Europe

- The Azure Traffic Manager will then respond to the DNS request with the CNAME record for the closest WVD Web or Gateway deployment based on the region it has discovered from the DNS server IP address, which in this case would be one of the European deployments that are in the Azure North or West Europe regions

- This CNAME is then resolved to an A record and then an IP address which is then stored in the DNS caches (depending on their configuration) and then it is finally passed back to the original end user device so it can connect to the service.

As you have probably now worked out from the above explanation, this is fine for the users in the UK office and the France office too; as they are in fact as close to the Azure North & West Europe regions as the UK is.

However for the users in the India office, they will be connected to the WVD Web or Gateway service in the Azure North or West Europe regions. This is clearly not ideal. Especially as there is now a WVD Web and Gateway deployment in the Azure regions based in India now!

Will changing the UK DCs DNS servers to use the Google DNS servers fix the issue for the India office users?

In short, no.

As the DNS request to Google’s Public DNS servers will still come from the UK DCs DNS servers so therefore we will still get sent to the European deployments of the WVD Web and Gateway services by the Azure Traffic Manager.

So how do we fix the issue for the India office users?

Well there are a few of ways we could do this however they both have pros and cons.

Fix 1 - Change the DNS forwarders on the UK DC DNS servers to Indian based public DNS servers

Whilst this would fix the issue for the India offices users, it would then cause the UK and France offices to suffer from the same problem but just in reverse.

The UK and France offices would be sent to the Indian deployment of the WVD Web & Gateway services.

So this isn’t probably the best idea

Fix 2 - Create a new DNS server in the UK DC that only uses India based public DNS servers as it’s forwarders and then set the India office devices to use this new DNS server

Whilst this will work, there’s a couple of things that aren’t great about this fix.

- It’s another DNS server to manage, patch and maintain etc…

- The latency of DNS requests and responses for India office users is likely to be quiet high.

- Just think that the traffic has got to transit across the corporate private WAN to the DNS server.

- Then the DNS server has got to transit across all the ISP peering to get to the Indian based public DNS server.

- And then the responses have got to get back to the DNS server in the UK DC and then back to the India office device that made the request initially.

- Then finally it can connect to the correct WVD Web or Gateway service

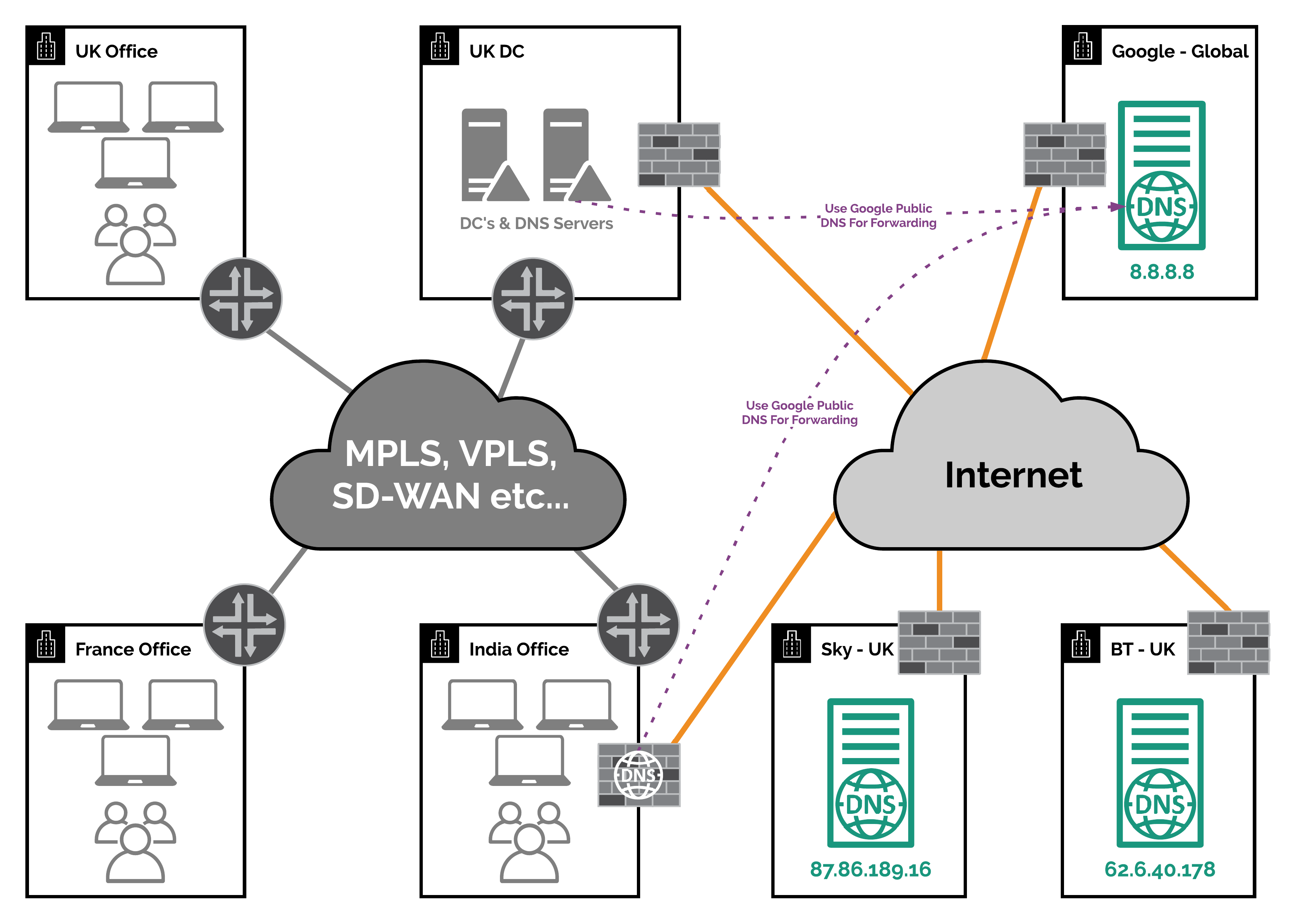

Fix 3 - Local Internet Breakout & Local DNS solution

This fix could be implemented across all offices and not just the one based in India, but for the purposes of this scenario I’ll only worry about the Indian office.

By putting a local internet breakout in the India office and either a DNS Server or DNS proxy solution on a firewall etc… (like you can on a Palo Alto NGFW etc…), you fix the second issue highlighted in Fix 2 (above). For DNS forwarding I would suggest using Google Public DNS as they uses Anycast routing to ensure you get to a local instance of their DNS service.

Whilst you also fix the main issue of ensuring your users get sent to the closest WVD Web or Gateway deployment as you are now using a local/country based DNS server.

This topology of all offices having a local internet breakout is becoming the new standard approach from what I see daily with my customers.

More and more applications these companies use are based in the cloud and require low latency, high bandwidth internet breakouts; which this topology delivers.

It obviously adds other challenges around security of perimeters as there are more internet circuits that you could be attacked from onto your corporate private networks. But that is a another blog post for another day.

If you want to see a blog post around this then comment below

Fix 4 - Build a local DC

This is pretty much the same as Fix 3 but instead of deploying the internet breakout and DNS server/solution in the India office, you would build a new DC in India and redirect the Indian office to use it for DNS and internet breakout.

However this is likely more costly than fix 3, so I wouldn’t suggest it personally.

Checking which WVD Web & Gateway Deployment you are being directed to by the Azure Traffic Manager and your DNS setup

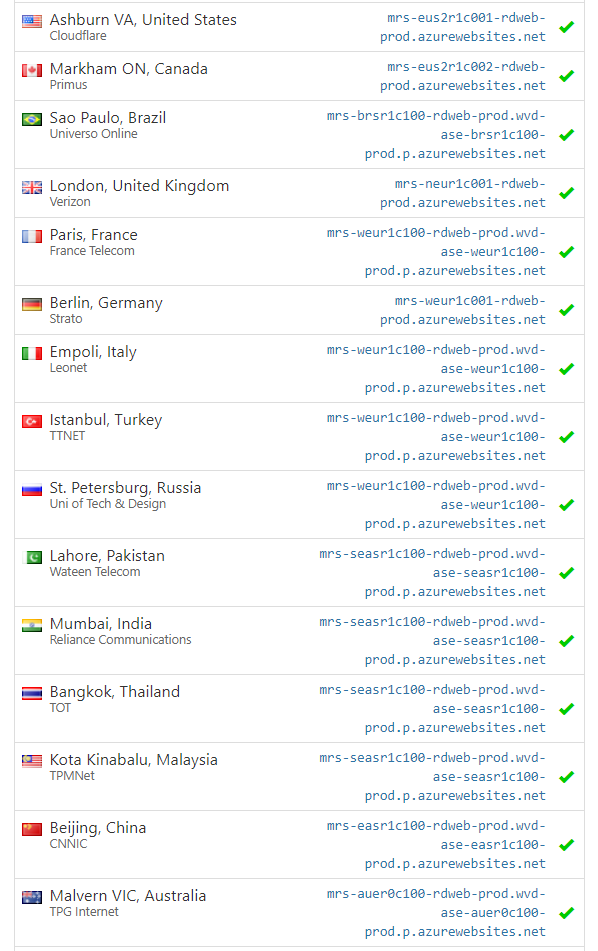

As you can see from the below screenshot, the Azure Traffic Manager really does respond with different WVD deployments based on the DNS server location where the request was made from.

I use whatsmydns.net a lot to quickly check DNS record propagation around the world, but it’s also great to show things like this. Go check it out!

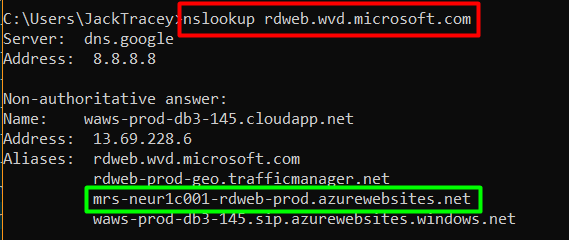

Or you can also use NSLOOKUP to check this from one of your end user devices to see where they are being directed.

nslookup rdweb.wvd.microsoft.com

As you can see the highlighted response in green shows my query to the WVD Web service being directed to the North Europe region by showing the ’neu’ abbreviation.

Summary

As you can see, it’s always DNS! (Sorry I couldn’t resist the joke)

But it really does play a huge part in the WVD user experience and is likely something that you haven’t considered or checked yet if troubleshooting a performance issue.

Finally as a side note, Direct Connect is being worked on by the product team which will connect users directly to the WVD Host Pool VM instead of the Gateways. But for this you’ll certainly want a local internet breakout in place to take advantage of this in the future. So you might as well get ahead!

As always leave any comments below!